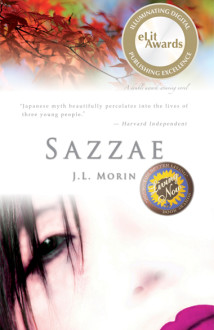

J. L. Morin’s Japan novel

Sazzae

Winner of the eLit Gold medal

and a Living Now Book Award

Sazzae opens the door to a wondrous cityscape where Japanese and American youth find each other in Tokyo. Discover the machinations of a lovers’ triangle, a painter’s inspiration, and an Untouchable’s dark secret through sensuous and evocative language. The pain and pleasures of Japan are remembered with lyric passion. J.L. Morin started writing Sazzae as a creative thesis at Harvard.

Fantastic praise for Sazzae

“Japanese myth beautifully percolates into the lives of the three young people.”

—The Harvard Independent

“Step into Sazzae and embark on an ethereal journey of lyrical imagery, manga-esque twists and turns, and intriguing characters at once both fanciful and engaging.”

— Alex Sanchez, Author of Rainbow Boys and Bait

Sazzae

by JL Morin

Release date: November 15, 2009

Genre: Visionary Fiction; Literary Fiction; Romance

Price: $14.95

ISBN: 978-0-615-28990-8

“Morin’s wit can be delicious. Her Tokyo actuality puts Morin several cuts above contemporary American novelists who bash Japan.”

— Canberra Times

“Her most delightful descriptions are of the intrigues in the personal lives of the protagonists.”

— The Harvard Crimson

“Like opening an expensive box of chocolates.”

— Sini Cedercreutz

Excerpt of the novel Sazzae, published in the Harvard Yisei Magazine

Shintaro’s bronze fist rose to the large metal 43. His fingers opened slowly, touched the numbers. Cold. He knocked.

“Just a minute,” came the voice from inside.

Shintaro straightened his jacket, realized he was smoking, put out the cigarette on the bottom of his shoe, and stuffed the butt into his pocket. The door opened.

“Hi,” Lois said. “What a surprise.”

Shintaro looked at his shoes.

“Um, how was the audition?” she quickly asked.

“The audition? Yes. I . . . blew it.”

“Oh. I’m sorry. Are you sure?”

“Yes. I forgot the song.”

“Damn. You probably didn’t have time to learn it.”

“No. I didn’t sing that song. I sang ‘Strangers in the Night’.”

“You did?”

“Yes.”

“Oh. Well. Come in.” She smiled and opened the door.

He followed her, not knowing what else to do. She looked especially nice today. He liked her best in her work clothes. She said she never wore skirts unless she had to. He wanted to say something about how pretty her sweater was or how nice she looked in a skirt, but all he could manage was, “Oh, you got a run.”

“Yeah, those subways. You know, so many people stepped on my feet. I think today is the record. I had to change stockings three times, and I was fifteen minutes late for work . . . .” The run started under her shoe and ended somewhere above her hemline.

Shintaro began untying his shoes.

“No, no, keep your shoes on. I’ve decided this is an American apartment. The floor’s dirty. Never mind. Come on.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes, it’s O.K. The floor is very dirty.”

“Oh.”

“It’s tea time. I’ll make some tea.”

“Thank you.”

Lois went off to the kitchen. Shintaro walked around the apartment in his shoes. There was really nothing to it. Large space, large windows, nothing on the walls except a black painting with Lois’s name on the bottom. He stared at this.

Lois returned with two cups and a pot of tea. “Oh. Don’t look at that.”

“Sorry I wasn’t . . . . Why?”

“It’s no good.”

“Is it yours? I mean, did you?”

“Yes, I painted it.”

“It’s . . . what is it?”

“Some people who . . . have a lot of trouble keeping their feet on the ground.”

“They lives in the Floating World.”

“They live.”

“They live.”

“Yes,” she said. She sat on the couch and poured the tea. “I thought your generation didn’t know about that stuff.”

“Yes. But my grandfather love that stuff.”

“Yeah? What else?”

“I don’t remember, just you can leave the Floating world by . . . medi —”

“Meditation.”

“Yes. Meditation.”

“Or death?”

“Yes. But that’s not . . .”

“Practical.”

“Plactical?”

“What else does he say?”

“He think Japan is under the ‘Curse of the Green Snake.’ It’s Mishima. My grandfather likes the military.”

“And what is the ‘Curse of the Green Snake’?”

“I don’t know that word in English.”

She handed him the dictionary. Shintaro sat down, took a sip of tea, and flipped through the pages. “The theory or doctrine that ‘p’ ‘h’ ‘y’ ‘s’ ‘i’ ‘c’ ‘a’ ‘l’. What’s that?”

“Physical.” She tried to touch his chest, but he turned away.

“Physical well-being and worldly possessions con . . . constitute the greatest good and highest value in life. That’s ‘materialism’.”

“Hm. Maybe it’s a good thing that you’re not going to become a teen idol.”

“Yes, my grandfather must think so.”

“Does he know?”

“Yes, he discovered it today. But he doesn’t know I failed at the audition.”

“You didn’t tell him until today?”

“A kind of.”

“Why not. I mean, I don’t really think he’d be that angry considering that it’s the only way to become a singer in Japan.”

Shintaro took a sip of tea. He was blushing. “Yes,” he said, and said no more.

Lois leaned forward over the table. “Well why then?”

“It’s very difficult,” Shintaro said.

“Fine. I like difficult things.”

“You can’t understand it.”

“Come on, that’s not fair; you’re not trying.” She set her cup loudly down on the table.

Now Shintaro almost wished he hadn’t come, was about to make an excuse to leave. His hand reached for the dictionary instead. After looking up a couple of words, he closed the dictionary, put it down on the table, and repeated something a few times under his breath.

“What?” Lois said.

“American people are free to invent his own past.”

Lois thought about that for a minute. “So?”

“So, Japanese are not.”

“I don’t get it.”

“Told you,” he said.

There were certain things she wished she’d never taught him. “Come on.” She sighed, drew back her hair and tried again. “That’s too vague. You have to apply it.”

Shintaro picked up the dictionary. He looked up ‘vague,’ and ‘apply.’ “‘Apply’ is like ‘plactical’?”

“Yes.”

“I see.” His eyes drifted from the page to his fingertips, and followed the bones of his fingers up to his wrist. Three o’clock, his watch read. He lifted it to his face. “It’s late. I better go.” Shintaro stood up.

“Wait a minute,” Lois said.

Her eyes were big and deep.

“How are we supposed to be friends if you don’t trust me?” she asked. “Friends trust each other.”

Shintaro opened the dictionary again. Trust: firm reliance on the integrity, ability, or character of a person or thing; confident belief; faith. Reliance on something in the future; hope. To have confidence in. To believe . . . . He closed the dictionary, was silent for a long time.

The telephone rang, one, two, three . . . eleven times. Shintaro looked up at Lois to see if she was going to answer it, but she just stared at Shintaro.

“O.K., I trust you don’t tell ANYONE. Even Maximilian.” Shintaro’s breathing was hard.

“I promise,” she said.

“Because I never told anyone. Not even Japanese, or Maximilian. You promise?”

“I said I promised. Don’t you believe me?”

“But this is real. No jokes.”

“I’m not joking.”

“O.K., well . . . .” He drained his cup. “Can I have some more tea please?”

She poured him another cup.

“A long time ago, before the Tokugawa Emperors of Japan — do you know about them?”

“Yeah, sort of.”

“Those were the emperor who kept the peace for hundreds of years. But before them even was a —” He looked up a few words in the dictionary, “a class of people called . . . burakumin.” Shintaro took a deep breath. He was surprised at himself for saying that word. “Do you know what that mean?”

“No.”

“Oh.” Relief. He could still leave and be safe. The words forced their way to the surface: “That mean . . .” He looked into the dictionary. “. . . that mean ‘untouchable’.” He fell silent. His hands were shaking.

“I don’t see what that has to do with anything.”

“Don’t you see? ‘Untouchable’ is the worst thing in the world. No one can discover that.”

“You mean your family was untouchable?”

“I mean ‘was’ and ‘is’, are the same in Japan. ‘Untouchable’ is dirty, not clean, like animals, people thinks.” Now he was shaking uncontrollably all over. “I am untouchable. That’s what I mean. I AM UNTOUCHABLE.” He turned his back to her.

Lois set down her tea cup, walked over to him. “Come on, that must have been so long ago. You are beautiful. Those silly superstitions don’t apply to you.” She put her arms around his shoulders.

He started, pushed her away. “Don’t touch!” he said.

“Look, I don’t believe those things. They’re not true.”

“No, you will be dirty.”

“I’m already dirty,” she said, stepping in front of him.

“This is not a joke.” He turned away again.

Her voice was small. She said, “Let me hug you.”

Shintaro stared at his feet. She pulled him close, wrapped her arms around his neck and squeezed him hard.

He stood frozen. The thin white arms finally around him. And she might as well be getting her feet stepped on in the subway as he lay in his futon. Might as well be teaching his English class. Or flirting with Maximilian. “You don’t understand,” he whispered. She might as well be in America.

“No, you don’t,” she said, and laughed, still holding him tight against her breast.

He did not cry.

The phone rang again. “Answer it,” he said.

Lois answered it. “Hi Maximilian . . . . Yeah, I heard it didn’t go so well . . . . Really? That’s great! . . . . No, no, he’s here. Yeah. I’ll let you talk to him. Just a minute.” She set down the receiver. “Shintaro, Maximilian is on the phone.”

“I . . . don’t want to talk.” He turned his face to the window.

“Just for a second? He has some news.”

“No.”

“Please?” She handed him the receiver.

“Hello what.”

“Sorry,” Maximilian said.

Shintaro held his breath.

“SORRY!” Maximilian said. “I didn’t know about the photos. It was Masami’s little prank. I guess he took it too far.”

Shintaro listened.

“I don’t want to argue with you. There’d be no one on my side. Look, Masami gave those photos back to Kato. He’ll tell you. Kato said he wants you anyway. Are you listening?”

“Yes.”

“You’re supposed to go to his office on Tuesday. I gave Lois the address. Got it?”

“I understand what you said.”

“Well are you going?”

“I don’t know.”

“I know how you feel. I really am sorry. I don’t know what Masami could have been thinking. O.K.?”

Shintaro exhaled.

“Well, put Lois on.”

Shintaro watched Lois take the phone, heard Maximilian’s voice, “Is he going to do it?”

“What?” Lois asked.

“Be a teen idol.”

“How should I know? They have to offer it to him first.”

“They will. I’m gonna give them a great stock tip. What they’re going to make on fish stock will cover the cost of promoting ‘Tomorrow’.” Although Maximilian didn’t like giving away his best stock tip, the idea of Shintaro failing the audition was unacceptable. He deserved to succeed, and Maximilian had to make sure it happened. Once the boy had the deal under his belt and had built up a little self-confidence, things would be different. They would both be comfortable, and then they’d see how they felt. “Come on. I know he talks to you. Is he going to accept? What’s going on with him? Tell me the truth.”

Shintaro slipped through the apartment door. He walked down the street humming the hunt song quietly to himself.

Shintaro sang, and lo! the falcon, as it burrowed into the snow. They sang the falcon hunt song as they marched back down the trail to their village. The untouchables. They hung the game on the pole at the center of the houses. The ancestor warmed himself by the fire pit. They told stories. It seemed a young girl had saved the life of a samurai with a blade of grass. When it was the ancestor’s turn, he simply unfolded his wonderful sash. The hunters stared. He hung it on the pole with the shiny falcons. What luck. They sang. As if it were alive, the purple sash flew with the singsong on the wind. Its silken skin captured the red and orange fire in its coolness, like the hottest of flames, like a tongue, like a flag hailing the great cause of the world. Indeed, there were many spirits hovering beyond the halo of fire, and as their number increased, the youths felt their boundlessness. It was the day of remembering dead souls. The sash fluttered triumphantly as if heralding a long-forgotten spirit. The men fell silent. Such a sash could only belong to royalty, and was not for them. Each knew the others’ fear. They could answer only with their own, and disbursed. Shintaro sang in a low voice as he walked along.

Autumn was something Shintaro knew, with its golden leaves. Autumn made Shintaro feel he should be back at school. He was wearing his burgundy sweater. He had told her. He got out of the station and rode his moped along the country road under a tunnel of trees with a feeling of enormous well-being. He felt for the first time that no matter what happened, he would be all right. His bike dipped into a puddle. He splashed the leaves on the roadside. He rode on into the sunshine past a field. He felt extraordinarily safe, with such a high level of ki, that he wondered if the energy had gathered around him because of some impending danger. But why shouldn’t he be all right? He knew he was not alone. He felt a presence, and expected to see his ancestor when he looked into the mirror on his handlebars. No one, of course. He vaguely wondered what was going to happen next, but he felt so reassured by the presence that he didn’t question it. He was already on the road. The trip would be long. He came to the end of the woods, and turned off the dirt road and onto a main road. When he arrived at the house, the angel had gone. ![]()

About the Author

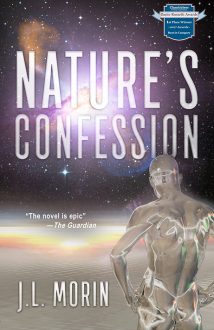

JL Morin grew up in inner-city Detroit. She proffered moral support while her parents sacrificed all to a failed system. Wondering what the Japanese were doing right, she decamped to Tokyo. Her debut Japan novel, Sazzae, won an eLit Gold Medal, and a Living Now Book Award. Her second novel, Travelling Light, was a USA Best Book Awards finalist, and her third, Trading Dreams, became ‘Occupy’s first bestselling novel’. Her climate fiction novel, Nature’s Confession, won first place in the Dante Rossetti Book Awards; a Readers’ Favorite Book Award; a LitPick 5-Star Review Award; and an excerpt received an Honorable Mention in the Eco-Fiction Story Contest, published in the Winds of Change anthology of eco-fiction. Her second cli-fi novel, Loveoid, is a Cygnus Sci-fi 1st place winner, among others.

Her cli-fi novels are on course syllabi at many universities. Ivy League professors have facilitated discussions with JL Morin’s writing, and it is discussed in textbooks, such as Science Fiction and Climate Change: A Sociological Approach, by Andrew Milner, and J. R. Burgmann, 2020, published by Oxford University Press.

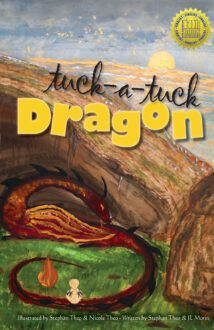

Her most recent work, Tuck-a-tuck Dragon, is a diverse rhyming children’s book illustrated by children throughout their childhood from the ages of 2–21.

JL Morin’s writing draws on a breadth of experience. She traded derivatives in New York while studying nights for her MBA at New York University’s Stern School of Business; worked for the Federal Reserve Bank posted to the 103rd floor of the World Trade Center; presented the news as a TV broadcaster; and she is adjunct faculty at Boston University. Morin’s fiction has appeared in The Harvard Advocate and Harvard Yisei, and her articles and translations in The Huffington Post, Library Journal, The Detroit News, European Daily, Livonia Observer Eccentric Newspapers, The Harvard Crimson, and Agence France Presse while she worked in their Middle East Headquarters.